“Is there some persistence of time that opens up at the end, or beyond the end, or even a strange poetic function of the end?”– Judith Butler

I didn’t want to start here but I am preoccupied by it. There is a moment toward the end of Werner Herzog’s film Lessons of Darkness where we are finally given the relief of an extinguished oil spout shooting into the air, all minky and black garnet. The film is “set” in the burning oil fields of Kuwait at the culmination of the first Gulf War. Feeling gut sick but mesmerized by the wicked sublime repetition of so many towering fiery spouts, the sight of a simple black geyser as the film comes to a close is a confusing relief. Texas tea and feckless hillbillies come to mind. And then, right on cue, in come the white male workers with their Seventies beards and strange mirrored goggles. I am uncomfortable with my predictable attraction to them, but this is, after all, a film about bad romance.

Are they astronauts? Are they working out a modern rain dance on Mars? Are they just loving the alien or now that the heroes have come is something shitty happening? Then one of the white men gracefully, flippantly, runs up and heaves a flame into the black geyser and it re-ignites. This is pure horror. Gluttonous and macabre. I begin wondering about the order of the film’s images, about this desert storm’s narrative sequence outside the film. Time.com tells me, “As the 1991 Persian Gulf War drew to a close, Hussein sent men to blow up Kuwaiti oil wells. Approximately 600 were set ablaze, and the fires–literally towering infernos–burned for seven months.” Okay. So then why does Herzog have this footage of this white guy doing what had supposedly been done by Saddam Hussein? Oh. Right. Right. That is the low-hanging fruit, as a friend of mine likes to say.

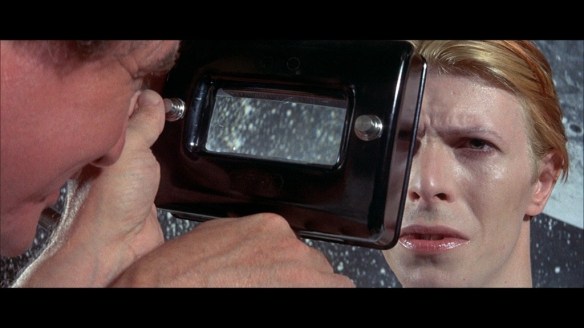

I often get this line from Bowie’s Station to Station, an album as much about lessons of darkness and desire as any other text, stuck in my head: “It’s not the side effects of the cocaine/I’m thinking that it must be love.” Bowie asserts, I am having a real epiphany. This certainty is born out of something other than drug mania. But, precisely in what way is drug or any other mania not real? Who anymore is above some sort of pharmaceutical, surgical, or virtual extension of your own particular spark? Hashtag no filter is a sweet impossibility, but wasn’t it always already the case? Isn’t this what we talk about when we talk about mediation? The song goes on: “It’s too late/to be grateful. It’s too late/to be later than. It’s too late/to be hateful. The European canon is here.” This is the return of the thin white duke, no? Making sure white stays.

I often get this line from Bowie’s Station to Station, an album as much about lessons of darkness and desire as any other text, stuck in my head: “It’s not the side effects of the cocaine/I’m thinking that it must be love.” Bowie asserts, I am having a real epiphany. This certainty is born out of something other than drug mania. But, precisely in what way is drug or any other mania not real? Who anymore is above some sort of pharmaceutical, surgical, or virtual extension of your own particular spark? Hashtag no filter is a sweet impossibility, but wasn’t it always already the case? Isn’t this what we talk about when we talk about mediation? The song goes on: “It’s too late/to be grateful. It’s too late/to be later than. It’s too late/to be hateful. The European canon is here.” This is the return of the thin white duke, no? Making sure white stays.

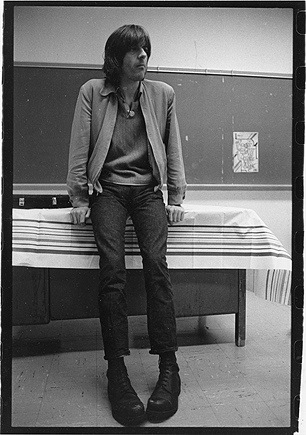

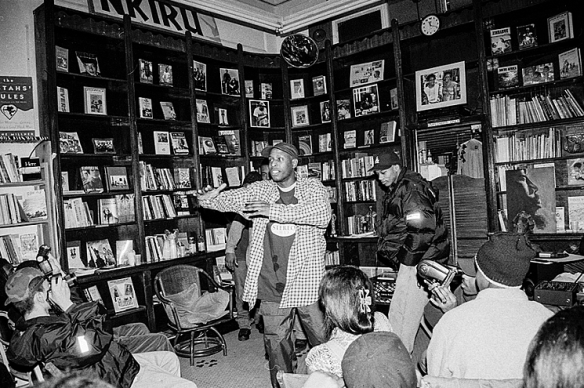

Sitting in a tiny desk off in that cramped ground floor isolated corner classroom of Turlington Hall–always too many desks, too many students crammed together, I meticulously copied “Black men loving black men is the revolutionary act” into my notebook while the lights were still down. This was the first of many times I would watch an old VHS copy of Tongues Untied in a dark room with students–is there any other way to come across it? I was taken by Marlon Riggs’s citations of poems by Essex Hemphill. His name, the lines of poetry open wounds like pop music, his skeletal body, eyes about to pop out. I wanted to know more. This was maybe 1996 so my only recourse was to go to the stacks of Library West. It worked like this: I looked up “Essex Hemphill” in one of the big library computers. Then on a little scrap of paper left next to the computers by library staff, with a stubby pencil I wrote the call numbers for the sources in which I might find him. Then I made my way up the stairs to the bookshelves that matched the numbers. Everything I was to know about him was, for that day, limited to these shelves and these numbers. I pulled out old issues of Callaloo until I found him. Then I would heave my pile up to the 5th floor, in the middle of “Russian” Literature, sure that no one else would go up there on purpose. And then, I would just read. Aimlessly. Finally the lights would start flickering around midnight and then I would go find all the other kids who liked to dance drinking beer somewhere.

Sitting in a tiny desk off in that cramped ground floor isolated corner classroom of Turlington Hall–always too many desks, too many students crammed together, I meticulously copied “Black men loving black men is the revolutionary act” into my notebook while the lights were still down. This was the first of many times I would watch an old VHS copy of Tongues Untied in a dark room with students–is there any other way to come across it? I was taken by Marlon Riggs’s citations of poems by Essex Hemphill. His name, the lines of poetry open wounds like pop music, his skeletal body, eyes about to pop out. I wanted to know more. This was maybe 1996 so my only recourse was to go to the stacks of Library West. It worked like this: I looked up “Essex Hemphill” in one of the big library computers. Then on a little scrap of paper left next to the computers by library staff, with a stubby pencil I wrote the call numbers for the sources in which I might find him. Then I made my way up the stairs to the bookshelves that matched the numbers. Everything I was to know about him was, for that day, limited to these shelves and these numbers. I pulled out old issues of Callaloo until I found him. Then I would heave my pile up to the 5th floor, in the middle of “Russian” Literature, sure that no one else would go up there on purpose. And then, I would just read. Aimlessly. Finally the lights would start flickering around midnight and then I would go find all the other kids who liked to dance drinking beer somewhere.

Likewise, if I had watched Lessons of Darkness back then, I would have had to dig until I found a conversation in a film journal, maybe even on microfiche, about the guy who ignited the oil. But none of my teachers ever screened it. I never saw it at our downtown art theater, the Hippodrome. No one I knew happened to bring it home from the Office of Instructional Resources. We watched it a few weeks ago on the couch courtesy of some Netflix-type service, and then I googled the scene and discovered on a film blog that he did it because Herzog asked him to: “…as Herzog explained at a festival screening, he simply asked the firefighter to reignite a well for the camera and he agreed because the hard work was done. It was the heat from months of burning that made the fires so hard to put out and it took weeks of dousing the surrounding area to cool the ground down enough. Snuffing a fresh fire would be easy in real life.” No bike ride to the library. No photocopies of my evidence. No late night drink and conversation afterwards. Just me and my smartphone. Took about two minutes.

Those pins above are what Jane Austen used to edit manuscripts. I believe the note at the bottom reads, “pins out marriage bonds.” Editing. Sometimes when we are building an arrangement, I hear Emily say, “just put the whole branch in. We can edit it later.” The idea is to edit the branch to make it look more natural. In order to tell a story about what actually happened, Hertzog stages all sorts of things. Frank Lloyd Wright brought the outside in with Cherokee Red, Le Corbusier had Vert Noir, Yves Klein International Klein Blue. Translations of sound and vision, all of them.

I keep trying to use these pieces to either resuscitate memories through this singsong voudou (pins for making) or to lay them to rest (pins for editing). I start out thinking, this is how I put it away, but once it’s out of the chest I want nothing more than to put it on. They both are and are not mine to wear. The surrounding area has been doused. The ground is cool enough. I was camping upstate last weekend on a magical farm with lightning bugs and Icelandic poppies and camera crews and retakes and fire and no fire. I watched how it works. So what is the harm in reignition for camera work, if the story is there? Snuffing a fresh fire would be easy in real life, right? If the hard work was done?

I keep trying to use these pieces to either resuscitate memories through this singsong voudou (pins for making) or to lay them to rest (pins for editing). I start out thinking, this is how I put it away, but once it’s out of the chest I want nothing more than to put it on. They both are and are not mine to wear. The surrounding area has been doused. The ground is cool enough. I was camping upstate last weekend on a magical farm with lightning bugs and Icelandic poppies and camera crews and retakes and fire and no fire. I watched how it works. So what is the harm in reignition for camera work, if the story is there? Snuffing a fresh fire would be easy in real life, right? If the hard work was done?