Instead of the corny doo-wop dudes in media res, the song begins with a steadily moving bass line and zaps of feedback. One could be forgiven for expecting Little Peggy March’s strident, stalkery anthem to kick in and for imagining that she’s transmitting the massive, fuzzy, cranking transmission from Atlantis or some massive rusty frigate on which she assumed the eternal position of an arsenic green sea witch figurehead, with glowing red eyes lighting the way, forever roaming the subtropical gyres in search of her love, just as she once swore she would: There isn’t an ocean too deep, a mountain so high it can keep–keep me away–away from my love! I LOVE HIM! I LOVE HIM! I LOVE HIM AND WHERE HE GOES I’LL FOLLOW! I’LL FOLLOWI’LLFOLLOW….

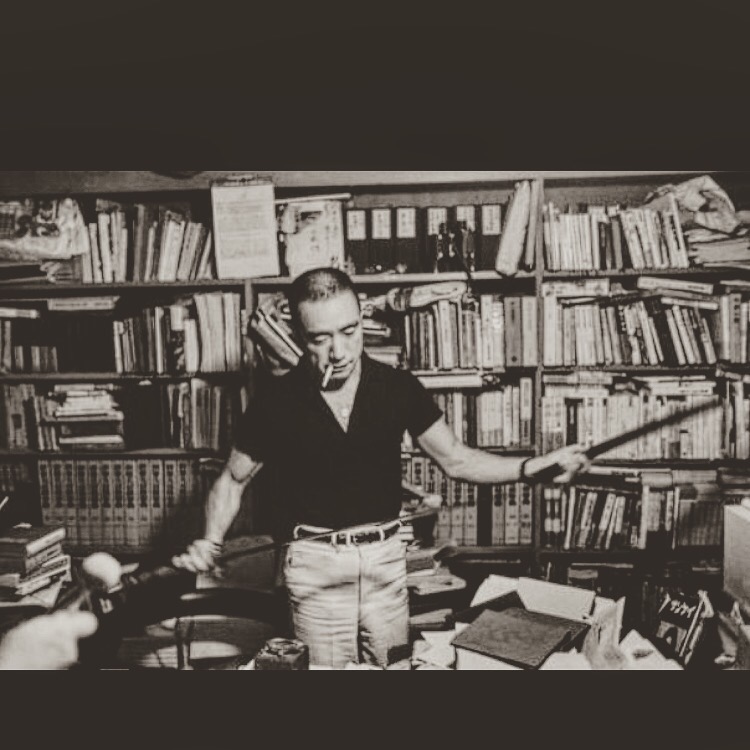

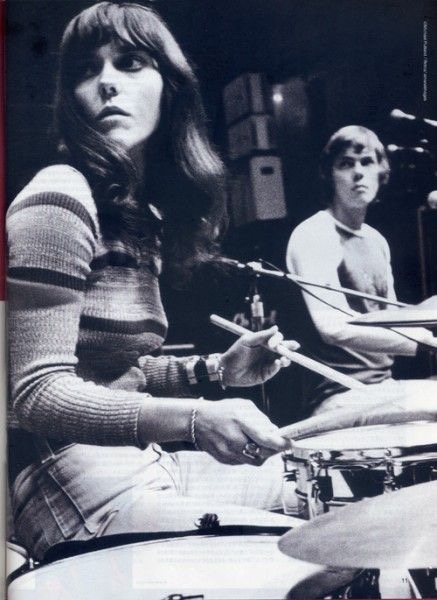

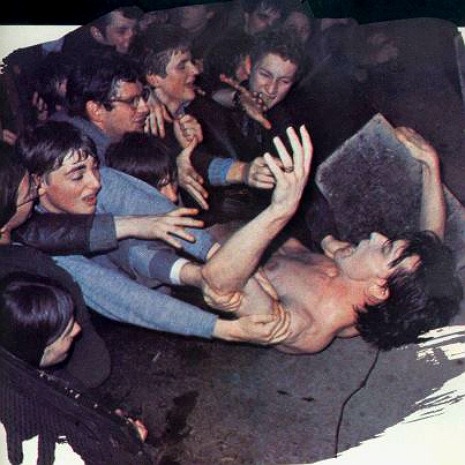

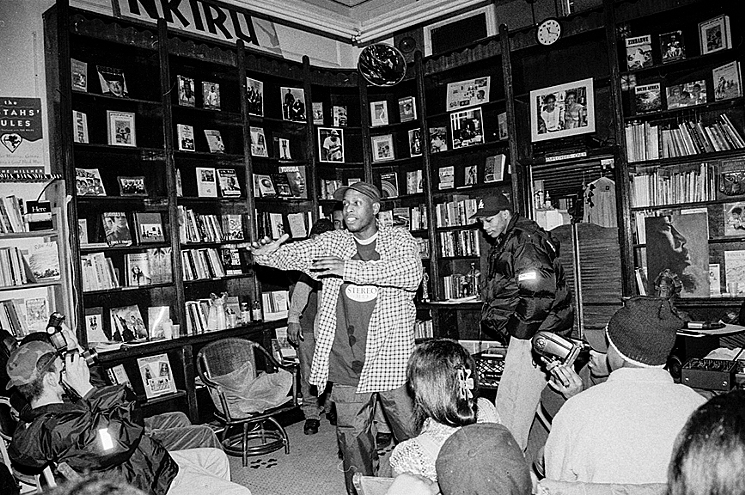

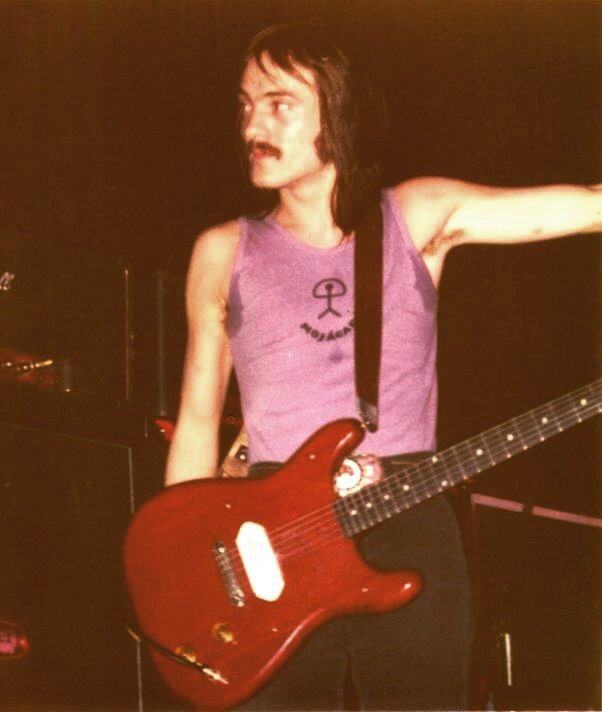

The drums kick in. The guitar screeches in fits and stops, wiping itself on everything that moves. Muffled lyrics sigh, grumble, accuse, and disabuse the listener’s expectations of transmission. Maybe the true soundtrack of the famous Enchantment Under the Sea dance is mutating back-to-from a future that never emerged, or from an atomic past that never stops going off. This is certainly not, in any case, Peggy March. This song, led not by proclamations of love but by the rubbery persistence of an unstoppable bass line growing faster and hungrier, its insistance maybe churning the guitar into an actual chainsaw slicing its way out of the hull of this situation they’re in, which the lyrics describe as another kind of love, one that can’t be satisfied, one that feels like murder, one that lives in deep night, heavy night, on and in a night that is heavier than a death in the family. Fathoms under this sea, instead of the spectacle of a dorkwad time-traveller pretending to have invented something, a very different sound, one that at once outlines and shreds Frank Porcel’s instrumental “original” song “Chariot” (1961). In the murk of this night, what is infinitely more “original” is this ghastly, blinding doppleganger, and it begins to seem that Frank and Peggy were the copies all along, trying to dredge this sunken version out into their sanitized renditions via some crazy funhouse mirror, and between the echos maybe the point is that there is no beginning, just an electrified mirror. The song, then, as it turns out, is not called “I Will Follow Him.” This is “The Night, Assassin’s Night,” and it was performed on earth by a Kyoto noise band named Les Rallizes Dénudés, whose lineup changed many times but was always organized by Mizutani Takashi, beginning in or around 1967. What came first? Which is the original? We think we’ve moved beyond these questions, but they have also been resuscitated and mobilized to distract us now more than ever.

In contrast to opinions confidently asserting the platitude that nothing is more boring than other people’s dreams, I get excited when people try to recall their dreams to me. This could be because I have a sleep disorder that gives me relentless access to my own dreaming, and I am usually too overwhelmed by the closeness of my own dreams to record them. Occasionally, I write one down and try to recombine it into something like a poem, but it seems impossible to capture the weirdness of the original in my translation, so I just save the notes. Sometimes when I’m jogging, I set what I can remember of the dream to whatever I’m listening to, and insert a jump cut here and loop a scene there to match the song until I’m left with some jittery glitching Brakhage-kernal. Perhaps images and music, rather than words, are the better route for dream-mining. But the real question is, what is meant to be mined? Are my real thoughts (not exactly the correct word here) in the dreams, or when I’m trying to recall them?

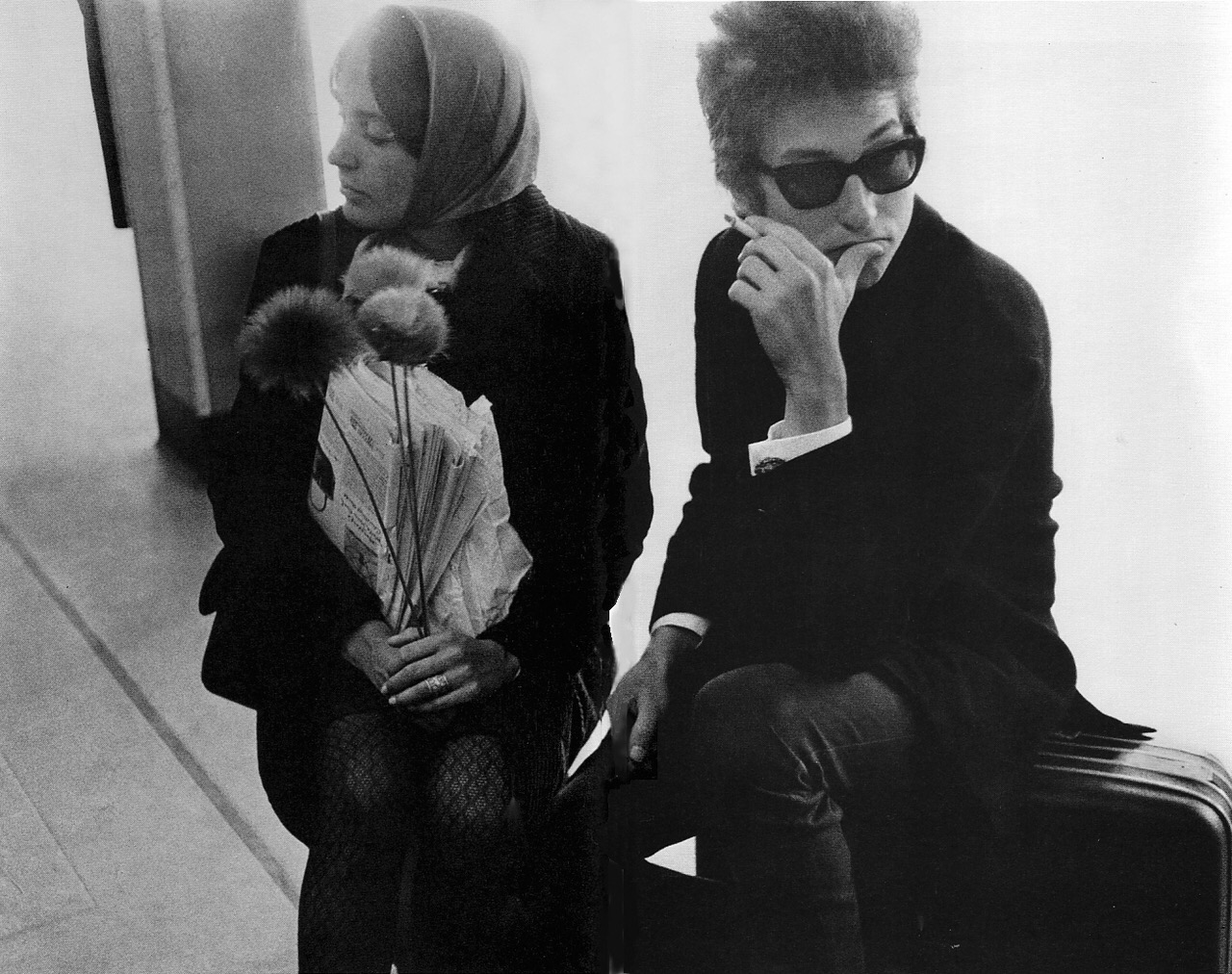

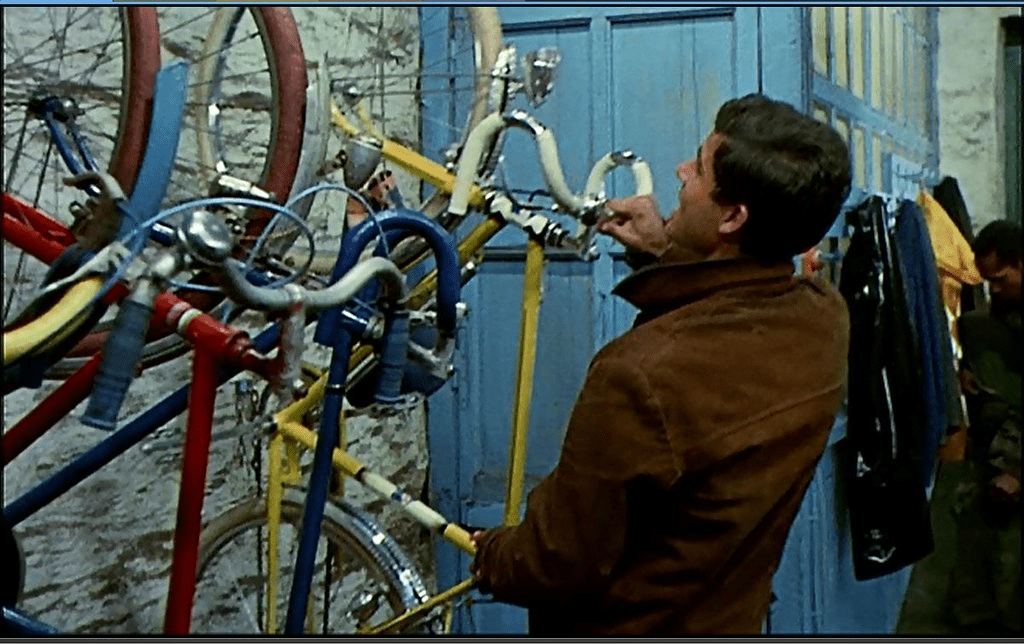

Equidistantly, a line of people slowly passes through a scorched yard. Each one moves along a path that rubs against a suburban chain link fence tangled in those electric blue morning glories that show up everywhere from vacant lots in Bushwick to trailer park trellises in the Panhandle. The walkers idle past a brazier smoking mandarin peels over matching neon embers as, like knots on a cord, they proceed. Their jeans are held together by patches in obvious joinery, and their thin shirts are denim with mother-of-pearl snaps. Uneven squares draped around their necks could be scarves or worn-out safety jackets. As they get closer, the little chains look like mink stoles made out of seaweed–expertly bustled with thread, in a mildewy shade of greeny-black. The first person has kumquat hair and carnation-bud lips. The next has a shawl dotted with blotches of red and yellow calico and flashes of sun-bleached lifevest tangerine. Here and there, his clothes are sullied like they’d been used to polish shoes, or as if he had just pulled out from under a car. The person following him wears a jumpsuit like Guy Foucher’s in The Umbrellas of Cherbourg.

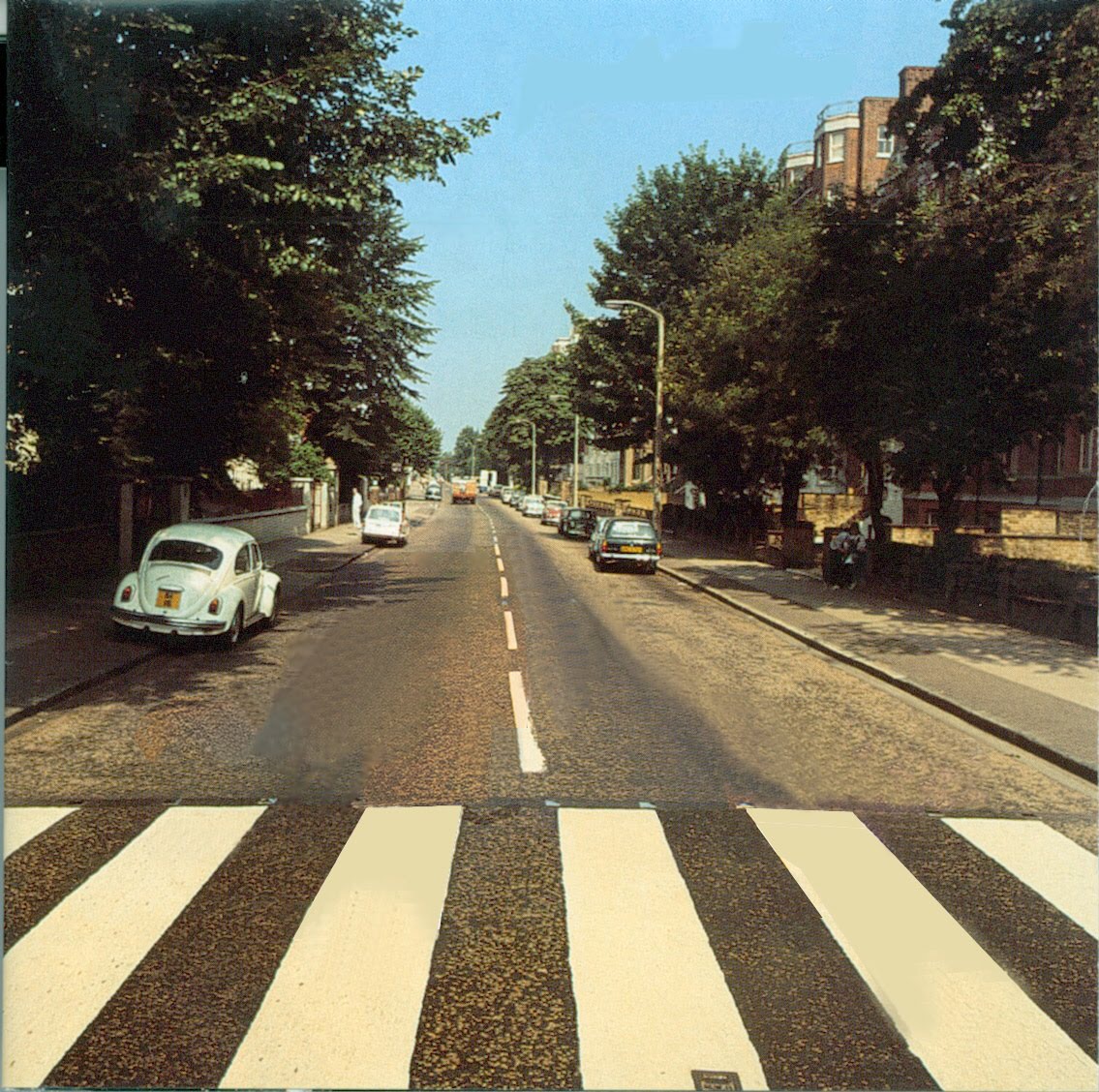

Around the time I saw this film for the first time, all of the guys I knew had these prewar bicycles that were painted in sparkly colors like guitars, and I loved to watch them gracefully glide onto the little seats, like they were mounting metal horses, as they disappeared up the block. Back then, I absurdly imagined that they had learned how to do this by studying old French or Italian films, mimicking the way Foucher, the mechanic, soon-to-be-drafted and sent to Algeria, rolled out of the garage at the end of a shift, off to see Carmen with Genevieve. The wanderers in the dream look like the boys from the old bike gangs, but now they are just walking, and they need a soundtrack. I hum the bassline from the LRD song described above. The reverb becomes jump cuts, and the echoes do their marrionettey dance. Nothing about that song is meant to soothe the listener. Maybe this is the estrangerie my dream wanderers have shown up to remind me: desire shouldn’t walk through the yard like a zombie, it should feel/sound/look both like diving into the wreck and like riding it back to the surface. Preferably, all at the same time. How can we keep from repeating the final scene of Umbrellas?

The dream dude with the black stole walks toward me over the crunchy, frost-bitten grass. His hair is thick with fat, etoliated curls, and his eyes are a few shades lighter than the sky. Against the fence, we crouch to the ground, pressing into each other. Without warning, the interlude moves to a loft. A band is playing, then pianos fall from the top floor. Everyone is running, and the sound is like whole fists banging on the lower keys – a Looney Tunes soundtrack with the telltale sudden, jaunty violence.

As we fade out, Lou Louie Louie Reed reminds me,

And Romeo had Juliet.

And Juliet had her Romeo.

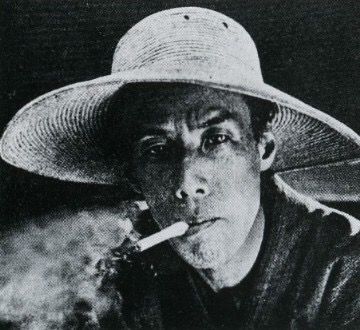

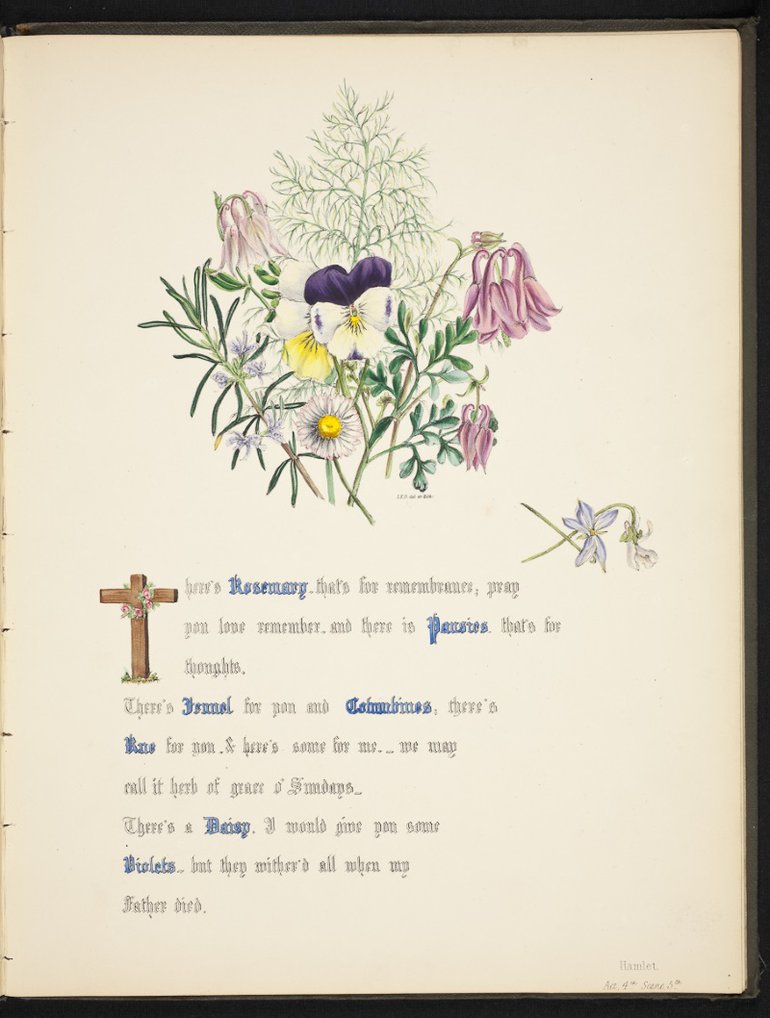

But it’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream, and the way it seeps into so many cultural objects that reached me before I’d even read or attended the play, that I love. The stories within the play’s stories and Shakespeare’s flaunting of the fact that Romeo and Juliet are modifications of Ovid’s Babylonian lovers from the Metamorphoses: Pyramus and Thisbe. The character who intrigues and confuses my classes is the “Indian child,” who the king and queen of the fairies are fighting over, and whose tantalizing presence drives the conflict of the play. This was the role Kenneth Anger (according to some, the inventor of the music video — albeit through a détourned, black magickal lens) claimed to have acted in Max Reinhardt’s 1935 classic Hollywood adaptation. Anger also used the name of another character from the play, the shrewd and knavish sprite, the hobgoblin or fairy Puck, that merry wanderer of the night, for his production company:

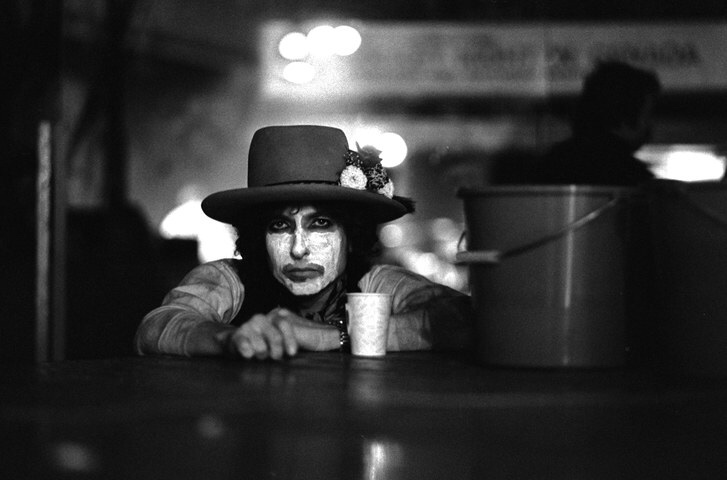

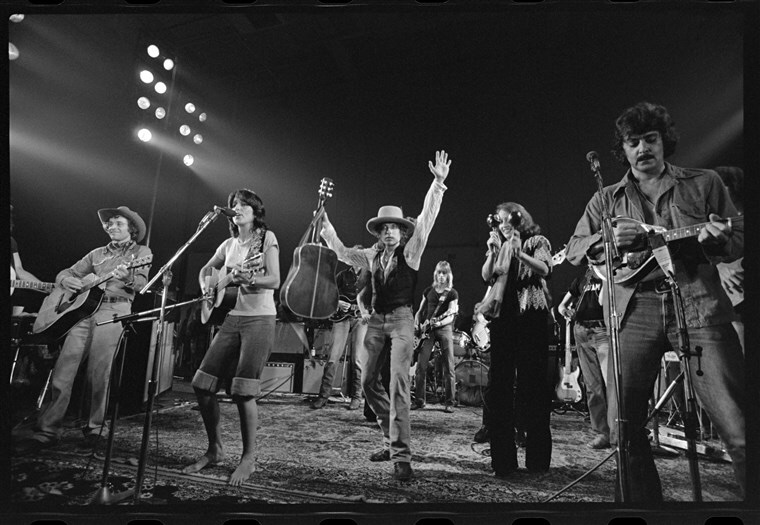

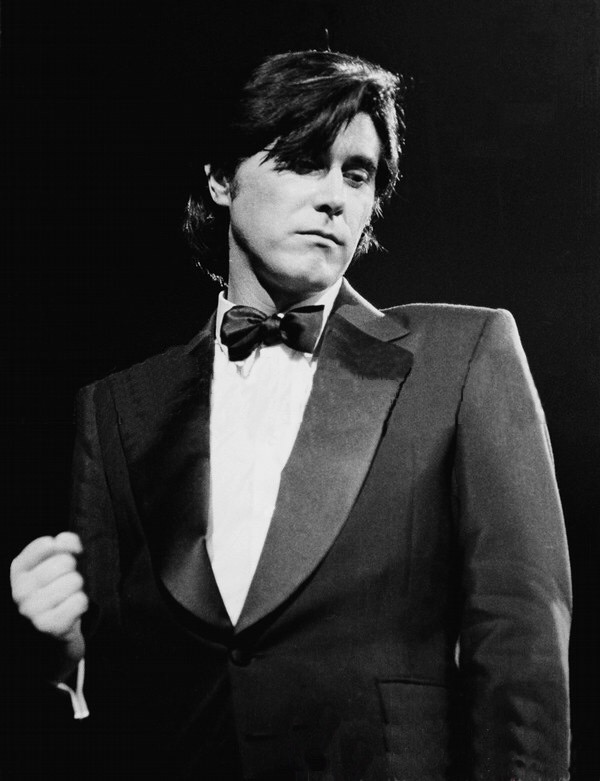

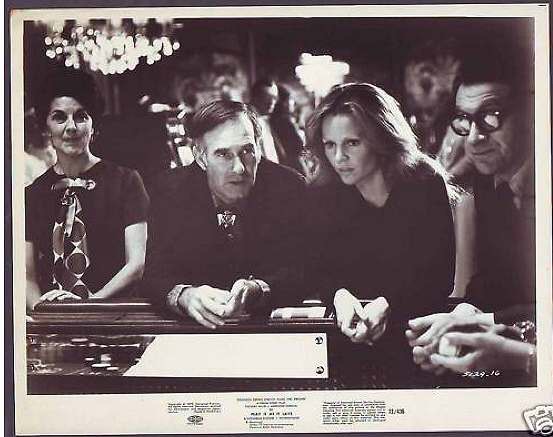

In the first and bottom photos, from Reinhardt’s film, see the child. How old is this “child?” students ask knowingly, more disturbed initially by his age than his birthright. What might the child stand in for? Colonialism, global trade, the puppeteer of ideology in its many guises? Shakespeare knew how much trouble a child could be used to cause. They ask, “Why does Oberon even want him?”

As long as the fairies continue to bicker over the child, the natural world remains out of sorts. Famines are driven by rotted crops, and blooms emerge out of season. These tiny creatures who could nap in an acorn shell are crucial to the maintenance of planetary equilibrium. The reader’s thoughts wander off; maybe, these things don’t just run on their own. Maybe certain things, things I can’t see, must be in place for them to function…? Is something there where I thought there was nothing?

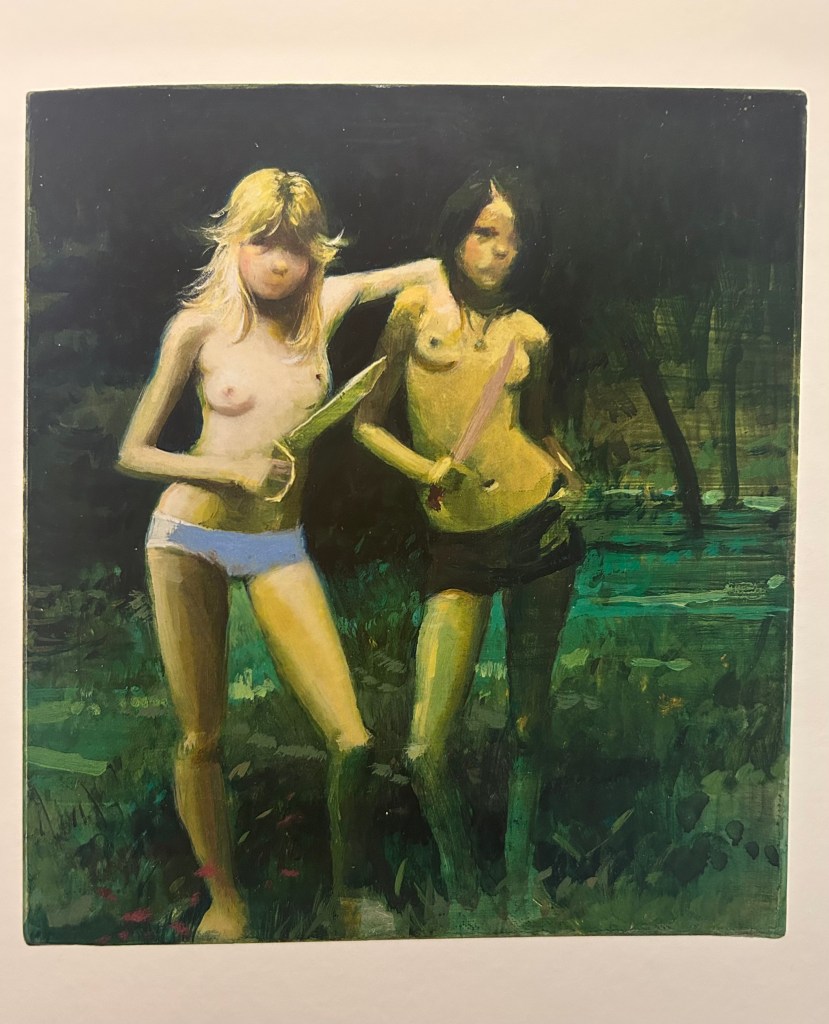

I wish Anger had made his own short, experimental film version of the play to work out his desire to have played the child. No dialogue, just a few key scenes synced to a soundtrack perfectly enunciating the drama. His Oberon as a leather daddy and his Titania looking like a Manson priestess.

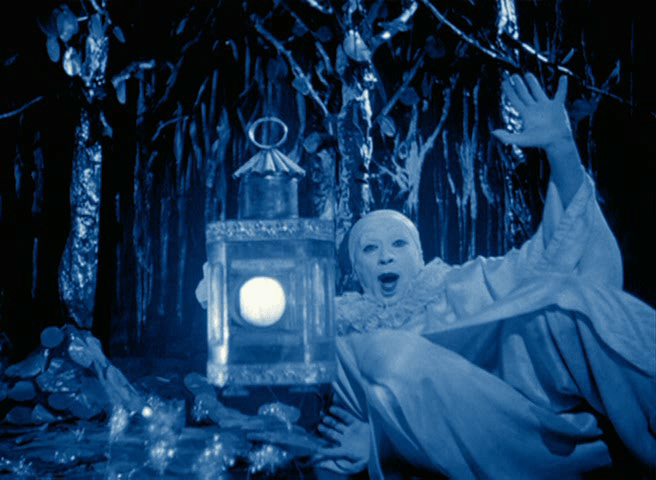

But wait, he almost did. Rabbit’s Moon (1950/1971/1979) could be an interlude in the play. With its icy little children wielding a mirror and a foil-wrapped guitar, the harlequin, the dancing Columbine with her fairy antennae, poor Pierrot in shimmery white, and the magic lantern projecting a film within the film whose phantasmagoria can be walked right into, it’s impossible not to see shades of Reinhardt’s Midsummer. The impossible rabbit-in-the-moon of all longing (played by Anger’s pet rabbit Nunu) appears in the grove and wiggles his nose. The dream shows Pierrot how to cross the lines. The harlequin fiddles with this knowledge, and Pierrot blacks out into a garland-wrapped moon-land, then flops back into the original glade like a dead doll. The End.

Is the dream a cheap foil, a pathetic wish formation, or is it the place of vital work? In Midsummer, the “dream” resolves all conflict, but it is not a dream, not exactly. It is a spell cast by Oberon and administered by Puck. It is a hallucination that allows the characters to do what they are supposed to do: get married. It (the dream potion: a homeopathic of the wild made from the juice of the pensée sauvage!) is primarily retrieved to bewitch Titania into, no matter how Victorian the production veers, “loving” a donkey and losing her adopted child.

In Rabbit’s Moon, Pierrot seems to love the moon itself more than Columbine, and the insatiability of the longing turns him into a floppy sack. But now finally, the object of desire is not the issue — the model for representing desire is, I think, what we need, with Pierrot’s determination, to pursue. Townes Van Zandt, of course, claimed (and his pet parakeets confirmed) that “If I Needed You” came to him, fully formed, in a dream. But I think David Lynch’s confession that the only image he dreamed in direct form was the ear that ignites the conflict in Blue Velvet is closer to what we are looking for. The small clues will unglue the big ideas because the pieces we need (now, yesterday) have already been dreamed. Do you want it, or is Oberon really pulling the strings? What if the sleep the pensée sauvage allegedly brings is actually the thought we are looking for–the clue to the place where we can/have awaken/ed? The absolute dedication to the possibility of the dredge of the (aesthetic-political) process is what we must twin. And when we see our twin, we might find that the myth was wrong all along — rather than a harbinger of death, the doppelganger (our double walker) might be the future we so desperately need.