i finally fixed the lock on my mailbox last week. Walking over to the locksmith by Five Leaves that is somehow always packed, purchasing the correct lock, making it back home, going upstairs to grab the tiny screwdriver i use when i need to change a battery for one of Jonas’s toys, running downstairs again and figuring out how to screw the pieces in–maybe took me an hour. Maybe. The thing is, it’s been broken since November. My key snapped in half in the lock, and i just left the door open, but my mailman finally stopped delivering the mail because he decided it wasn’t safe. So then i had to fix it, because i evidently can’t not receive my mail. My Dad joked, “You need a man around the house.” i rolled my eyes deeply into the phone. “DAD. i fixed it. MYSELF.” It’s not that i couldn’t do it. This was more of a soft protest. i just. Wouldn’t. Perhaps i do need someone or something around the house, but probably not in the way he meant. i’ve already got way too much trouble getting out of bed.

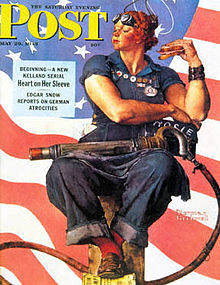

Some years ago, i worked in a Feminist bookstore. Yes, we were almost exactly like the Portlandia skit, and it actually was a tiny haven of awesomeness. One of our bestselling items was a “Rosie the Riveter” poster. Rosie, that powerfully ambivalent icon of untapped female potential. With a flexed bicep, she proclaims “We can do it!” We can win the war, we can defeat the Japanese (as the little pin with an image of a Japanese woman’s face [she has tiny horns] on her collar suggests), we can do work usually undertaken only by men, we can work with African American women, we can become financially independent. i think the poster (and the mug, and the pins) sold so well because shoppers liked the possibility of rallying behind this image that we would now read as unabashedly butch. “We” is no longer nation; it is now gender, and the specifics of Rosie’s origins are generally lost in translation. For me, Rosie represents the complications of consumer feminism. She has been productively co-opted by Feminism and no longer is really a symbol of patriotism, but a more general sense of a woman’s ability to…do…it. Yes, we can do it–but wait: what the hell is “it” anymore?

Everyone i know from grad school remembers the one text that began her obsession with critical theory. She was a good undergrad, loved her English classes, but then one day she read x and from that point on had a new understanding of politics, words, and, well, she became an academic. Life outside the diamond became a wrench. In a letter, Emily Dickinson asked, “If I feel physically as if the top of my head were taken off, I know that is poetry. These are the only ways I know it. Is there any other way?” An ex-boyfriend told me once that he couldn’t sleep for days after the first time he read Walter Benjamin’s “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” and i was in. That he had very long eyelashes and could quote Drugstore Cowboy with an impeccable timing that always made me giggle didn’t hurt, either. For me, that entry in the course pack was Louis Althusser’s “Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses.” ISAs for short. When i worked at Isa, i thought of the acronym every time i walked in the door, even though the restaurant’s name was taken from the Estonian word for “father,” which is not so far off the mark, either.

Instead of saying “sex,” i pretty much always say “doing it.” i generally understand this as one of my many Seventies affectations, but i do like the way it retains some recognition of sex as productive–not necessarily in the way Rosie might have understood production, and not in the way we generally refer to “reproduction,” but in an Althusserian sense: as ideology. In his essay, Althusser discusses the quintessential role of the reproduction of conditions of production for Marx, and “fleshes out” his understanding of ideology, announcing his maxim: “Ideology represents the imaginary relationship of individuals to their real conditions of existence.” Yesterday, walking down Wall St with my son and two friends, we simply could not believe the ratio of police to protesters. Here were bodies moving through a space defined negatively by police, and while this is technically an example of what Althusser would call “repressive” state apparatuses, the way in which the arrogant, anticipatory presence of police on the one year mark of Occupy Wall Street “made visible” relationships to power we might usually allow ourselves to dismiss as imaginary was staggering. Yes, we can do it–pretty much however we please, but how do we translate the expansive possibilities for sexuality that have been painstakingly won over the past 50 years into dynamically new lived relations that continue to ask the question of how not to pass on this story?