“When I was growing up, all the women in my house were using needles. I have always had a fascination with the needle, the magic power of the needle. The needle is used to repair the damage. It’s a claim to forgiveness.” Louise Bourgeois

Before my son was a week old, I put him in a car seat and we rode in a cab all the way from Williamsburg to the Guggenheim. My Mom was leaving the next day to go back to California, and I wanted her to see the Louise Bourgeois exhibit. He cried for most of the time we were there, and the entire way back. I never made it to the top of the rotunda, but the trip wasn’t really about me seeing the art. I needed my Mom to see the work, and I wanted Jonas to be there, even if it meant nothing but discomfort to him. While I was pregnant, I had gone to see a documentary film about Bourgeois: The Spider, the Mistress and the Tangerine. I was taken by the ways that both her ambivalent relationship to family and motherhood and the vibrancy of her anger drove her artistic productivity. In one interview, Robert Storr suggests, “She generates energy, and she generates psychological energy. She’s also a vampire. She sucks up psychological energy.” She explains of herself, “It’s not the emotions themselves, but it is the intensity—the emotions are much too much for me to handle, and that is why I transfer them, I transfer the energy, into sculpture. This applies to everything I do.” During the portion of the film that discusses her steel and bronze spider sculptures, Laurie Anderson’s song “O Superman,” right around its 6 minute mark, pipes in. Bourgeois has just told us, “The spider is the mother.” We see one of the gigantic spiders, and the song’s unmistakable pulses begin, followed by Anderson’s hauntingly distorted voice with its flat demand: “So hold me Mom, in your long arms.” I immediately began to cry. I still have my Mom’s Laurie Anderson albums, and I vividly remembered her playing Big Science during my childhood. This song wasn’t really about the Superman I knew, but it did suggest to me that my Mom was a kind of imperfect, preferable superhero(ine).

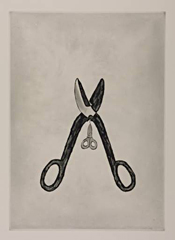

The needle, thread, and spiders (but no webs—perhaps they don’t last long enough). Repair as artistic method. This is familiar to readers of queer theory, especially of Eve Sedgwick and her suggestion for “reparative,” rather than “paranoid,” readings. The idea that the material of one’s life might be mended through creative production is less combative than vampirism and less sure of itself than merely paranoid critical readings. Even in those first days, I wanted my own parenting to attempt a kind of renovation, not only of my childhood and my relationship to my family, but also of cultural fantasies I had been taught about parents and parenting. Showing my Mom the work was a way of saying thank you for the unusual, difficult, queer, invaluable upbringing my parents gave me. i also wanted to suggest that thinking about attempts to represent these experiences teaches us how else we might behave.

“So hold me, Mom, in your long arms. In your automatic arms. Your electronic arms. Your petrochemical arms. Your military arms. In your electronic arms….”